Optimism for Integrated Care Delivery in Europe

Last week I attended the International Conference on Integrated Care (ICIC18) in the Netherlands, leaving with a sense of anticipation that Europe is on the cusp of a monumental healthcare reform. However, the realist in me understands that it will take many years for Western Europe’s healthcare systems to make the transition to delivering value-based healthcare.

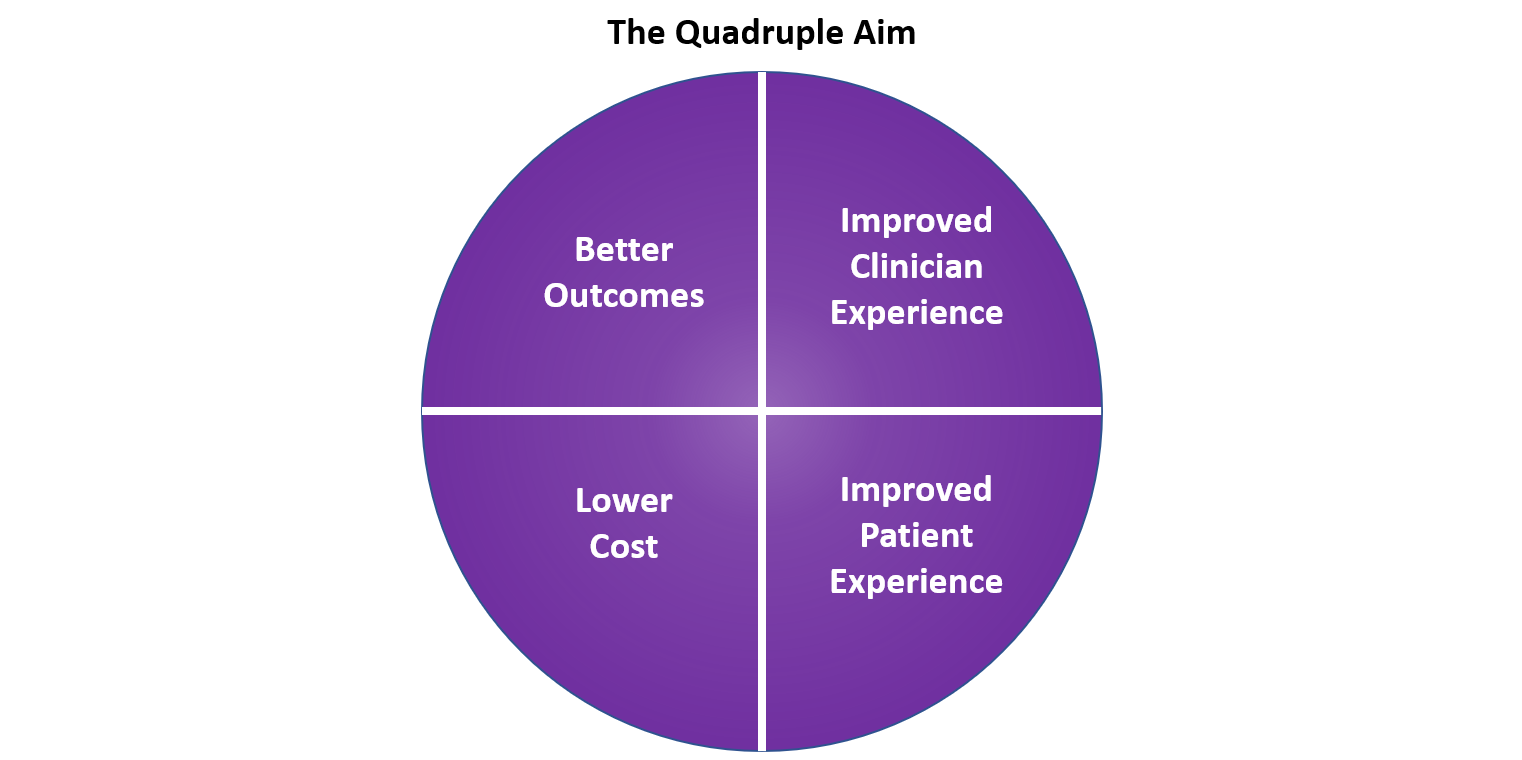

The quadruple aim (image below) was mentioned numerous times at the ICIC, highlighting what providers within Europe want to achieve when implementing integrated care. However, outlining these goals is the easy part. Huge challenges remain across Europe in terms of the organisational restructuring, payment reform, and implementing ways to measure success that will be needed to achieve the quadruple aim. Each of these points was discussed in detail throughout the conference.

With that in mind, care providers in Europe continue to struggle with a lack of coordination across regions and verticals. In addition, small providers looking for change are often dwarfed in size by large payer organisations who aren’t necessarily keen for change from the current fee-for-service (FFS) models.

In a population-based approach, the payer passes their risk over to the providers who are incentivised to reduce healthcare costs through the improved management of their population’s health. Savings made are then shared between the payer and provider. However, payers can be reimbursed for taking on higher risk patients, reducing their incentives to exit from a rewarding FFS model. Let’s take Germany as an example.

The Current Situation

As with most developed countries, the German healthcare system is under strain due to a rise in multimorbid patients and an ageing population. This demographic requires more complex treatment where good coordination between healthcare, social care and mental health providers is often essential. However, separate payment models for inpatient and outpatient care (as well as long-term and social care) make it particularly difficult to align incentives between sectors.

Instead of providing funding through taxation, citizens finance a statutory health insurance (SHI), or sickness funds, with contributions through their employer’s payroll. The government is responsible for the accessibility and quality of care; however, regulation is delegated to national associations leaving regional governments with minimal roles in the financing or delivery of healthcare.

Across the sickness funds, funding is pooled and then redistributed through capitation, with chronic illness rates and age-related demographic factors taken into account. GPs and ambulatory specialists in Germany are typically self-employed and are able to negotiate their own contracts with the sickness funds on a FFS basis. Acute care payments are based on guidelines provided from diagnosis-related groups (DRGs) who use a fixed-price capitation model. The current model provides little financial incentive for providers to shift towards a value-based payment system, whilst also limiting interactions between inpatient and outpatient settings.

Slow and Steady Wins the Race?

Despite the lack of incentives outlined above, in 2006 the Gesundes Kinzigtal region of Germany was one of the first in Europe to develop a population health management-based approach to healthcare provision. The project was set up between two sickness funds in the region and Optimedis AG, a healthcare management and technology company.

Optimedis set up a data warehouse to normalise and aggregate various types of care and insurer data in the region. With this, the population was segmented by age and morbidity of patients per physician, providing analysis into the outcomes between varying treatments and individual care givers. This allowed Optimedis to highlight potential gaps in care between practices in the local area.

The initial analysis allowed Optimedis to create tailored disease management programs and distribute these across ambulatory providers to better manage chronically ill patients. To achieve this, financial incentives were provided to GPs who enrolled their patients onto these specific disease management programmes.

The project was run as a cost-saving model with the sickness funds, Optimedis and some care providers all benefitting from savings made in healthcare provision. Between 2007-2015, an estimated €35.5M has been saved against the risk-adjusted normal costs of care in Germany for the 33,000 patients included in the project.

The long-running success of the partnership has resulted in high levels of interest elsewhere, resulting in Optimedis taking numerous partnerships or consulting roles in the UK, the Netherlands and Belgium. However, despite the apparent success, it took Optimedis over 10 years to set up its next German project in Hamburg.

Before a cost-saving contract is devised, Optimedis will run initial analysis on the targeted population to assess whether savings can be made within the region. However, the data required to run the initial analysis is typically held by the sickness funds, who aren’t always able or willing to share data with a third-party organisation.

With the latest project in the Billstedt/ Horn regions of Hamburg, the population experiences below average life expectancy and suffers from high levels of morbid disease, driving the sickness funds to look for a value-based approach to improve outcomes within the region. The initial phase within the new project involves setting up walk-in clinics for GPs to refer chronically ill patients to and integrating an EHR into the regions.

A Different Approach

The ICIC18 conference was littered with examples of other European countries utilising PHM technology to support the development of integrated care networks. Examples include:

- In 2014, France invested €80M into setting up five digital care regions (or TSNs). These regions were selected to put in place an integrated care delivery networks for both inpatient and outpatient care settings. Further rollouts are expected to be announced over the next couple of weeks.

- In 2015, the Netherlands set up funding to promote the integration of local primary healthcare providers under one organisation (called GEZs).

- The UK has some of the best examples of top-down initiatives driving PHM in Europe. In 2015, the UK outlined its ‚ÄòFive Year Forward View’. This allowed care provider organisations to apply and become ‚ÄòVanguards’ for new care models including the integration of primary and acute systems. Global Digital Exemplar’s (GDE) were also set up to drive care through the use of digital technology and information. In addition, Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships (STPs) were set up between local councils and NHS England to build proposals to better manage their population. 8 of these were turned into an Accountable Care System (ACS), where healthcare providers take on the collective responsibility for PHM.

The overarching focus for government-led PHM initiatives in Europe is to support better coordination and shared responsibility in healthcare provision between local providers and give healthcare systems enough freedom and funding to implement change, something hard to achieve in Germany without the consolidation of small providers to generate change from the bottom-up.

So, Can PHM Work in Germany?

Germany’s latest reform came in 2015 through its Health Care Strengthening Act, which was aimed at removing barriers to implementing integrated care systems and provided additional innovation funds of ‚Ǩ300M. However, this still relies on local champions taking the initiative from the bottom-up, rather than driving organisational reform top-down, like the US or the UK.

In July, Germany’s E-Health initiative (providing a comprehensive nationwide EHR for both providers and payers) will be complete, potentially bridging some of the issues with data sharing between payers and providers. This could speed up the process of gathering data and setting up PHM projects for companies like Optimedis.

While providers want to reach the quadruple aim, PHM growth in Germany is forecast to remain limited to small initiatives focused on pockets of the population with high levels of chronic disease or elderly patients.

Germany knows it wants value-based care, it just isn’t sure how to get there.

PHM Market Report from Signify Research

The market analysis presented above is taken from research compiled for Signify Research’s report “Population Health Management – EMEA, Asia & Latin America – 2018” which is due for publication in June 2018. The report includes a deep dive into national and regional projects undertaken by local champions or the global vendors in 20 countries and regions. This report will also be accompanied with accurate market sizing and forecasts data and insight into initiatives and potential blockages for growth over the period 2017 to 2022.

For further information about the PHM reports offered by Signify Research please click here or contact Michael.Liberty@signifyresearch.net.